Stirring up health: Polyvagal theory and the dance of mismatch in multi-generational trauma healing

Published in Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, online November 2022, available at: http://www.tandfonline.com, doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2022.2148123

Dee Wagner dee@harborofdreamsart.com

Dee Wagner, LPC, BC-DMT, RSME, has worked as a counselor, dance/movement therapist, somatic educator, presenter and writer since 1993. Along with her artist husband, tai chi teacher son, yoga teacher colleague and massage therapist colleague, Dee created the polyvagal- informed multi-generational trauma healing method Chi for Two – The Energetic Dance of Healthy Relationship.

Dr. Orit Sônia Waisman orito@dyellin.ac.il; oritsonia@gmail.com

DMT masters department, David Yellin College, Jerusalem, Israel.

Orit Sônia Waisman, PhD, is a dance movement therapist, a Jungian analyst and a linguist. She headed the DMT Masters Program, David Yellin College, in the years 2005-2022. She teaches at the Israeli institute for Jungian psychology in the honor of Erich Neumann and is a member of its curriculum committee. Dr. Waisman is a senior lecturer; she has extensive clinical experience with various populations as a therapist and as a supervisor.

Abstract

In this article, author Waisman’s work with mismatch combines with author Wagner’s work with polyvagal theory to illuminate the dance of mismatch in healing multi-generational trauma. Author Waisman first became familiar with the concept of mismatch as it relates to gestures and words. During situations of conflict between Israeli-Arab and Israeli-Jewish students, Waisman noticed participants displaying gestures expressing meaning that differed from the accompanying words. Looking at mismatch through a polyvagal-informed lens, therapists can understand how mismatch relates to trauma. Polyvagal theory illuminates the anatomy that inhibits movement expressions as well as the intensity of the awakening of inhibited movement expressions. In this article, the authors suggest that mismatch of gestures and words relates to the inhibition of particular movement expressions—those which dance/movement therapists recognize as the “fighting” rhythms identified by Kestenberg and colleagues. Shahar-Levy (2001), a dance/movement therapist, speaks of coming out of "emotive motor memory clusters” (p. 379). Resmaa Menakem, author of My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (2017), speaks of the need to move through the pain to grow out of traumatic retentions. Therapists benefit from a deeper awareness of the mismatch moment when the “fighting” rhythms awaken.

Keywords - mismatch, polyvagal theory, multi-generational trauma, Kestenberg tension-flow rhythms

Introduction

This paper explores a delicate moment—the awakening of the Kestenberg “fighting” (Kestenberg Amigi, et al., 1999) rhythms after they have been inhibited by what Porges (2011) identified as dorsal vagal Shut-down. The authors claim that when therapists better understand the mismatch of this moment, they can more consciously offer the support that facilitates clients’ healing from multi-generational trauma patterning. Author Waisman became familiar with the phenomena of mismatch when conducting a study of nonverbal and verbal expressions in situations of conflict (2010, 2014, 2017). The data examined comprised a series of sessions between Israeli-Arab and Israeli-Jewish students. This study revealed that at times, during episodes of expressed conflict, when contradicting someone or some idea, and particularly when trying to cope with some new idea, some participants performed mismatch between gestures and words. In spite of the fact that the mismatch of gestures and words remained unnoticed to the participants, Waisman noticed that the mismatch seemed to arise out of an effort to come to terms with some content. This can be compared to the transition that Shahar-Levy and Menakem each describe in their own way. Shahar-Levy (2001), a dance/movement therapist, speaks of coming out of "emotive motor memory clusters” (p. 379). Menakem, author of My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (2017), speaks of the need to move through pain to grow out of traumatic retentions. Author Wagner has extensively worked with polyvagal theory, exploring its presence in the therapeutic relationship, and in familial and couples’ dances (2015, 2017; Wagner & Hurst, 2018). This article combines these concepts, and suggests a new theoretical framing of the mismatch moment when the “fighting” rhythms awaken after being inhibited over generations.

Picturing polyvagal theory

Porges (2011) created polyvagal theory based on his studies of the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve creates parasympathetic nervous system response. The parasympathetic nervous system creates calm. Porges noted that the vagus nerve has two major branches. One Porges identifies as ventral (front) and the other as dorsal (back). The prefix “poly” means more than one and thus the name “polyvagal.”

Vagus means wandering. The vagus nerve has many branches as it wanders from the brainstem down through the body, with many branches in the area of the heart and digestive organs (Porges, 2011). However, one major branch of the vagus nerve is myelinated (coated) and the other is not. The ventral branch is the myelinated one (Porges, 2011).

Ventral vagal nerve

The ventral branch affects the cranial nerves that create facial expressions, focus, the middle ear muscles’ ability to tune into the human voice, and the larynx’s ability to speak with vocal variety. This is why Porges (2011) calls the nervous system circuit related to the ventral branch the Social Engagement system. The vagus nerve as a whole creates calm in the body by braking activation—inhibiting various types of functioning—so we can tune into cues of safety or danger. It can be helpful to picture how the brake of an automatic car brakes the movement of the car—movement that occurs unless the brake is engaged. The ventral branch brakes activation in a way that creates an active state that is not Fight/Flight. Porges calls this state Play/Dance (Porges, 2011).

Wagner created a “Map” of nervous system functioning to help clients picture polyvagal theory and the pathway to healing trauma patterning. This “Map” is now a tool in Miller and Beeson’s Neuroeducation Toolbox: Practical Applications of Neuroscience for Counselors and Therapists (2021). When therapists show the “Map” to clients, clients can see that our bodies have two continuums of activation and calming. Helping clients see these two continuums of activation and calming normalizes trauma response.

Sharing this drawing with clients invites interaction that facilitates the awakening of movement expressions and continued movement through the Fight/Flight laced versions of those movement expressions toward an integration of those movement expressions into clients' movement vocabulary. Drawing available to download at chifortwo.com

Looking at the “Map,” clients can picture one kind of calm that exists as part of the circuit Porges (2011) calls the Social Engagement system and another that is the circuit called Shut- down. Therapists can first invite clients to notice how the character in the green box depicting Social Engagement system functioning looks contented, playful, and able to sense when it is time to rest and refuel. Therapists can then explain that when we sense danger, parasympathetic calming creates Shut-down, which provides a kind of calm that comes from dissociation. The character in the yellow box looks a lot calmer than the one in the red box, but in a more dissociative way than the character in the green box.

Looking at the “Map,” clients can picture the kind of activation that is part of the Social Engagement circuit—Play/Dance (Porges, 2011), then they can look at the character in the red box and sense the unique kind of activation helpful in times of danger—Fight/Flight. Because the engagement and release of the ventral brake on day-to-day activation can happen in milliseconds, Play/Dance provides more nuanced activation than the activation caused by the release of the fight or flight response. Fight/flight takes seconds for activation and requires time for the chemistry involved in fight/flight activation to resolve within the body (Diamond, 2015).

Dorsal vagal nerve

The dorsal branch of the vagus—the unmyelinated one—affects the body below the diaphragm. Like the ventral, the dorsal brakes activation, but in a much less nuanced way. Polyvagal theory helps us understand how the braking of the ventral branch affects the braking of the dorsal branch.

When the ventral branch of the vagus nerve brakes activation creating the active state Play/Dance, the dorsal facilitates replenishing rest and healthy digestion (Social Engagement system functioning).

When we are in danger, the ventral no longer brakes activation in the way that creates Play/Dance. Fight/flight activation occurs. If we feel trapped, the dorsal branch of the vagus brakes fight/flight creating Shut-down, which shallows breath and slows digestion.

From the animal observations of trauma expert Peter Levine (1997; 2010; 2017), we now know that the pathway out of the survival calm of dorsal vagal Shut-down to the replenishing calm of ventral vagal Social Engagement system involves the fight/flight response. Looking at the “Map,” clients can picture the pathway. Menakem (2017) describes this pathway when speaking of how we move through pain to grow out of traumatic retentions. Shahar-Levy (2001) describes this pathway as coming out of "emotive motor memory clusters” (p.379). Shahar-Levy observes that early traumatic episodes can consolidate into fixated body clusters.

Payne et al. (2015) share their clinical experience as a data point when they write that they have found significant shifts occur when a person is able to complete whatever movement was inhibited during the original traumatic event. They add anecdotally that the more closely aligned the movements are in therapy to those that were interrupted during the traumatic incident, the more profound the therapeutic shifts are observed to be. Joy DeGruy (2005), author of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome, Karr-Morse & Wiley (2012), author of Sacred Sick: The Role of Childhood Trauma in Adult Disease, and Menakem (2017) help us understand that trauma patterning gets passed down over generations.

Dance/movement therapy and polyvagal theory

Because cues about safety and danger are passed from person to person, dance/movement therapists have been interested in polyvagal theory since at least 2010 (Betty, 2013; Campbell, 2019; Devereaux, 2017a; Devereaux, 2017b; Gray 2017; Homann, 2010; Tantia, 2012; Wagner & Hurst, 2018). Before polyvagal theory, we used to imagine divisions of the nervous system that distinguished central (brain and spine) from peripheral (nerves that extend out from the central system). We pictured the possibility of voluntary and involuntary movement as a function of the peripheral system. Autonomic functioning used to be labeled involuntary and somatic functioning was labeled voluntary.

Now that we have polyvagal theory, we can consider the quality of the nervous system’s energetic communication between what we now think of as the Head-brain and the Belly-brain, the enteric nervous system (Contee & Wagner, 2021). The sensations during communication between the central and peripheral systems affect whether movement is voluntary or involuntary. Cues of safety and danger affect blood pressure, heart and breathing rates, digestive processes, body temperature, and sexual response (Devereaux, 2017a; Kolacz et al., 2019; Kolacz & Porges, 2018; Tantia, 2012).

The authors invite dance/movement therapists to take interest in the rhythm of the ventral vagal nerve’s braking of activation, which creates Play/Dance. We are trained to attend to tension-flow rhythms identified by Kestenberg and colleagues (Kestenberg Amigi, et al., 1999), particularly dance/movement therapist Susan Loman (Loman, 2016). Half of the rhythms are called indulging, and half are called fighting. The authors suggest that the “fighting” rhythms are key in the ventral vagal braking of day-to-day sympathetic functioning that creates the active state Play/Dance (Wagner, 2022). The first two “fighting” rhythms—snapping/biting and straining/releasing—show up in games parents play with their infants when parents sense safety. Games like patty cake that invite the “fighting” rhythms foster individuation within the dance of relationship (Loman, 2016; Wagner, 2015; Wagner & Hurst, 2018). Wagner’s article Polyvagal theory and peek-a-boo: How the therapeutic pas de deux heals attachment trauma links infant/parent interactions with client/therapist interactions.

Mismatch

As therapists look at the various studies of mismatch through the lens of polyvagal theory, they can better understand the mismatch that occurs between child and parent during the development of the “fighting” rhythms in infancy and mismatch that occurs when the “fighting” rhythms have become inhibited by dorsal vagal Shut-down and awaken laced with fight/flight.

Susan Goldin-Meadow and colleagues (Goldin Meadow, 2003) have studied extensively the phenomena of mismatch for several decades, concentrating mainly on child learning processes. They conclude that mismatch between words and gestures indicates some acquirement of knowledge and that mismatch is connected to the child’s achievements. One of Goldin Meadow’s conclusions was that mismatch indicates a transitional period, "...an index of readiness to learn...” (Goldin Meadow, 1997; 139).

The work of psychologist Edward Tronick introduces valuable findings that help therapists recognize the role of mismatch in early dyadic interactions (Tronick, 1989; Tronick & Beeghly, 2011; Tronick and Cohn, 1989; Tronick & Gold, 2020). This data demonstrates that in successful play interactions between mother and infant, the two are matched only approximately 30% of the time; the rest of the time they are slightly mismatched (for instance, a smiling mother and a neutral-faced baby). Tronick and Beeghly (2011) claim that early researchers were too entranced in what they termed "a Fred – and – Ginger model of dyadic synchrony as one of reflecting optimal functioning" (p. 111). Relying on studies of microanalysis of dyadic interaction, they present a model that is less harmonic. They describe what they call “messy” processes as what eventually enables infants to "form positive dyadic states and to expand their state of consciousness" (Tronick & Beeghly, 2011, p.14).

David McNeill, a linguist and a psychologist, explored the relationship between language and thought. In McNeill’s observations, gestures, unlike words, remained unnoticed. Participants did not seem conscious of having moved, although they were quite aware of having spoken (McNeill, 1992; 2000). Dance/movement therapy proposes a therapeutic environment where words and gestures are equally present and observed, inviting curiosity about clients’ relationship between words and gestures (Waisman, 2014).

In 2014, author Waisman presented the implementation of the concept of Mismatch to dance/movement therapists. She showed how mismatch, applied in a broad sense to include clashing/opposing movements, provides important content for therapeutic work (Waisman, 2014). Moments where the harmony is disrupted are opportunities for allowing new approaches to life. Consequently, it is not the role of the therapist to be constantly soothing and accommodating, on the contrary, moments of surprise and disruption of stability should be respected. Mismatch creates opportunities for the therapist to allow the client to open themselves to new/repressed material. Adding a polyvagal-informed lens, therapists can better appreciate the developmental mismatch that occurs when infant “fighting” rhythms create individuation within the dance of relationship.

Therapists can begin to appreciate the difference between developmental mismatch and the mismatch that occurs when inhibited “fighting” rhythms awaken laced with fight/flight. When parents activate with Play/Dance, they can play peek-a-boo with their babies in a way that babies only feel a potential for the fight or flight response. In Play/Dance, parents disappear, but reappear soon enough for babies to experience that there is no real danger. This experience of potential for danger, but no actual danger, is how babies develop their rhythmic braking of the ventral vagal nerve (Wagner, 2015). Staccato movements like the sudden reappearance of the parent can bring laughter. When parents activate with Play/Dance, they can play games that invite the biting/snapping rhythm like Patty Cake and there is no rupture in the relational dance and therefore no need for repair.

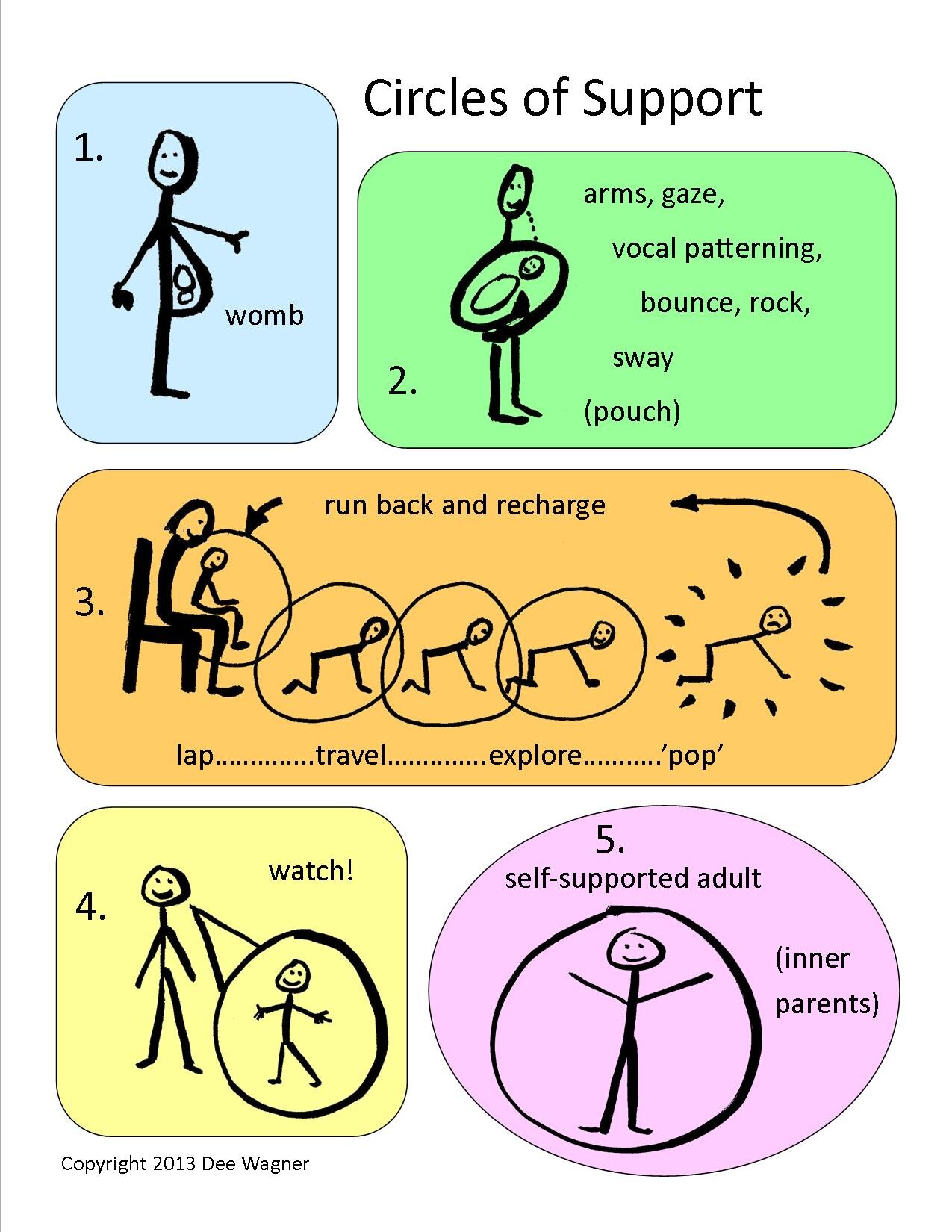

In situations of parental loss, and in situations where staccato movement could attract attention that could lead to danger, infant games like peek-a-boo and Patty Cake are not possible to do with parents activating with Play/Dance. The developmental mismatch, which creates the rhythmic braking of the ventral vagal nerve, can become inhibited and can lead to the inhibition of the “fighting” rhythms over generations. Without an appreciation of how the “fighting” rhythms foster individuation, family systems can fear oppositional movement, labeling it a disorder. Social messaging might suggest that movements with snapping/biting and straining/releasing rhythms are signs of disrespect. With a polyvagal-informed lens, therapists can hold Circles of Support for the awakening of movement expressions that have been inhibited by dorsal vagal Shut-down (Contee & Wagner, 2021).

Circles of support

At a 2014 workshop for the American Dance Therapy Association Conference called The Dance of the Social Engagement System, Wagner offered her drawing The Circles of Support, suggesting that therapy offers symbolic redos of the infant/parent interactions depicted in the Circles of Support drawing. Therapists may recognize in the drawing reminders of Mahler's Separation/Individuation theory and Stern's Emergent Self Theory. Stern argued with Mahler about what occurs in the first developmental period after birth (Peters, 1991)—what Wagner calls the Pouch Circle of Support. Stern's concept of the Emergence Self is depicted in the relational aspect of the Pouch, where a unique kind of co-regulation occurs as infants respond to caregivers' arms, gaze, vocal patterning, bounce, rock and sway.

Therapists who practice yoga will recognize basic yoga shapes in the drawing. Contee and author Wagner invite awareness of the connection between yoga poses and major developmental dances in their article The neuroscience of healing multi-generational trauma through body-based practices (2021). The yoga shape, which in English is often called Pose of the Child, can be seen in the Womb and Pouch Circles of Support. Both the posture that is often invited for meditation in which the practitioner is seated and attending to the positioning of the vertebrae, as well as the yoga shape that in English is often called cat/cow can be seen in the Lap Circle of Support. What English-speaking yoga practitioners often call Warrior poses can be seen in the Watch Circle of Support. Recognizing infant development in yoga poses supports the universality of the developmental dances in which the “fighting” rhythms facilitate the oppositional movement that creates individuation within the dance of relationship.

Sharing this drawing with clients invites dialogue about the value of the infant "fighting" rhythms for developing Self-support—what has been conceptualized as inner parents. Drawing available to download at chifortwo.com.

Looking at the Circles of Support drawing can help therapists and clients appreciate the fact that the “fighting” rhythms—especially snapping/biting and straining/releasing—transition infants from one circle of support to the next using these rhythms to individuate within the dance of relationship. These rhythms are found in abundance in situations of mismatch.

The authors propose that these rhythms become inhibited by Shut-down when support is unavailable due to lack of understanding of the rhythms. The “fighting” rhythms themselves are percussive. When they awaken accompanied by fight/flight, this awakening can be very intense. Therapists who do not have a polyvagal-informed lens that helps them recognize the awakening of inhibited “fighting” rhythms over generations might feel unprepared to support this awakening. If therapists are confused, it is likely that the client will shame the emerging “fighting” rhythms and their inhibition will be enhanced.

Dance/movement therapists are familiar with emerging movement. Therapists learn techniques for witnessing emerging movement in Authentic Movement and other dance/movement therapy techniques. However, without a polyvagal theory lens, the awakening of the fighting rhythms laced with fight/flight can feel like something has gone wrong. When therapists have a polyvagal-informed lens, they can recognize the awakening as a multi- generational trauma response and support the integration of the fighting rhythms into clients’ movement vocabulary.

Case study

Below, the authors present a case study from Waisman’s clinical experience that exemplifies the waking up of movement expressions inhibited by Shut-down, presenting the therapeutic process through the lens of polyvagal theory and the role of mismatch in multigenerational trauma healing.

Background and first stages of therapy:

Jordan was 47 when we began our therapeutic process. In our first phone conversation, Jordan had difficulty explaining why therapy was needed. Jordan spoke very fast and repetitively and yet with intonation that was monotone.

When we first met, the dissonance between Jordan’s harsh, poignant words and motionless body, touched me deeply. Jordan said, “Life has no meaning. Nothing gives me comfort. My family is not a source of joy.” Looking through a polyvagal-informed lens, I recognize Jordan had been living with many movement expressions inhibited by Shut-down as a result of multi-generational trauma. These movement expressions were hungry to awaken.

The therapeutic setting was stable, sessions were held on a weekly basis, an hour per week and I was available for short messages in between sessions. I was holding Circles of Support. Jordan would feel empowered to leave the session, knowing we would meet again at our regular time. When invited into movement at the beginning of the therapeutic process, Jordan’s expressions were close to the body, like a baby with no one to push into. This made sense as I learned that Jordan’s childhood was tainted by the father dying in a car accident. Jordan’s mother, the primary caregiver for the family, was often distracted and fearful. Jordan's grandparents (mother's parents) were Holocaust survivors. Jordan's descriptions of the interactions with them imply that they lived with many, many movement expressions inhibited by Shut-down. It certainly makes sense that the nuanced activation of Play/Dance would not be available to them.

A detailed description of a session:

About a year before we concluded our work, after four years of therapy, Jordan began to feel safe enough to enjoy my invitation of mismatch. In this session, Jordan’s movements with the “fighting” rhythms slowly awakened. Jordan moved through the fight/flight feeling of “Is this okay now?! Is this safe now?!”

I will now present in detail the appearance of mismatch in Jordan’s dance, and how the mismatch helped to integrate the “fighting” rhythms into Jordan’s movement vocabulary. In contrast to the usual depressive way of entering the room, there was a harsh way Jordan moved taking off shoes and stepping onto the soft carpet. Jordan looked at me as if reluctant to meet me and asked: "What's the use, ah? What's the use of me coming here, week after week, if I can do nothing to change my life, if things go on as they always do? You say you see that I'm stronger but I'm nothing, I'm nothing." The words stopped as Jordan started to inadvertently let a foot play with a soft ball that was on the floor. Looking up and pointing, Jordan asked, "Is this new?" referring to a bright colored picture that had always been hanging on the wall of my therapy room. "Actually no" I replied "how does it look to you?" "It's nice, I like the colors." I joined Jordan in movements that began to be more free-flowing, but in an abrupt way—a snapping/biting way. Jordan kicked at the cushions as if arranging them in order to sit down.

I invited, "What if you don't sit now? What if you wait a bit?" and I playfully threw a big blue physio ball. Jordan’s expression was one of surprise. Turning to me, Jordan caught the ball with a face that slowly widened until a smile appeared, like the sun behind a thick cloud. "So, you think you can throw balls at me?" Jordan asked with a new spark. Then, for a couple of minutes, we danced an exchange dance, where we each surprised the other by responding with unexpected movements. I now see the infant/parent play that was happening. Connecting and disconnecting with me, Jordan was demonstrating an energetic sense of self—individuation within the dance of relationship. Jordan seemed to be loving learning to play this game; it felt so natural!

I remember the moment Jordan hid the ball as if not wanting to kick it back to me. The exchange included laughter, for perhaps the first time I could hear Jordan freely laughing. After which, there was a sudden stop with Jordan announcing, “I’m thirsty.” In this moment, I was again in front of the little child who was fatherless at the age of 7, the child whose sorrow nobody acknowledged. I could sense a big burst of fight/flight accompanying these mismatch moves—a huge questioning, “Is this safe now?!” The mismatch laced with fight/flight was so intense that Jordan was vacillating between fight/flight and Shut-down. Our dance was offering a symbolic redo of Jordan’s early unfinished infant/parent interactions.

Jordan’s gaze turned inward, suddenly absorbed again in a sense of solitude. With this retreat, I could feel my own loss of breath, as I felt left alone. Jordan’s vacillation between fight/flight and Shut-down felt unbearable to me, but I sensed that this episode implied a new step in Jordan’s healing process. Polyvagal theory gave me an explanation of why I felt so shocked by the sudden shift. Fortunately, I contained my own sentiments and continued to hold Circles of Support. I approached and sat closer, a glass of water in my hand. Jordan took a sip of water and said, “I feel lost. I can no longer go into bed and turn my head to the wall. I cannot ignore things my children do anymore. I used to avoid their stories, their pains; now, I listen, and I feel overwhelmed. What should I do? How will I cope with all of this?” In this talk, I sat close, in a synchronizing pattern of movement and breathing.

After this session, Jordan began speaking up more and more in family and social gatherings, becoming more involved in the children's lives. Feeling less a victim, Jordan felt more valid in expressing opinions. As expected, Jordan’s close friends and family were surprised by the change and expressed their strong feelings of concern, expecting Jordan to respond by returning to Shut-down as the familiar polite, obedient and supposedly satisfied person of the past. Feeling a dependable rhythm of connection with me provided a symbolic redo of Jordan’s multi-generational lack of parental presence.

In a personal vein, I could recognize similar hungers within myself. I can see now how my own therapeutic journey helped me awaken my movement expressions, freeing my “fighting” rhythms, which had been inhibited by Shut-down, thus enabling my mismatch dance with my own therapist, several years before. I vividly recognize the fight/flight feeling of risk that accompanies waking up movement expressions from Shut-down. Looking back, I understand how my relationship with my therapist helped me keep moving until the risky movement expressions became part of my movement vocabulary. Having done this work myself, I held the needed support for the mismatch awaking for Jordan.

This case study shows how Wagner's “Map” and Circles of Support drawing, which illuminate the trauma healing path that awakens the inhibition of movement expressions from infant/parent interactions over generations add to the concept of mismatch to provide an explanation of Jordan's therapeutic process. Being able to dance with clients during the mismatch of awakening “fighting” rhythms is more likely when therapists look through the lens of polyvagal theory.

Conclusion

This article is the result of a combination of two dance/movement therapists’ extensive work with trauma-afflicted clients. We offer a polyvagal-informed lens through which therapists can better recognize the awakening of movement expressions inhibited by Shut-down.

The work of Porges is well-known and documented. The recognition of the anatomic details illuminated by polyvagal theory creates new understanding of trauma. Only recently have we begun to put the pieces together to recognize how multi-generational trauma causes certain movement expressions to become inhibited by dorsal vagal Shut-down over generations. Only recently have we begun to fully understand the fight\flight response that accompanies the awakening of those movement expressions. It is not possible to move directly from Shut-down to Social Engagement system functioning. There is a fight/flight feeling that asks the question, “Is this safe now?!” meaning, “Is it safe now to be myself?!” Therapists’ response helps clients determine if they have found safety.

Safety is a prime issue in any therapeutic setting. When clients' “fighting” rhythms have been inhibited by Shut-down over generations, clients lack the movement expressions that create a sense of safety. The “fighting” rhythms help infants develop the sense of individuation within a dance of relationship that creates the rhythmic braking of the ventral vagal nerve that signals safety.

The healing process includes a renewed experience—a symbolic redo of infant/parent dances that heal multi-generational trauma. These redos occur when therapists are able to celebrate clients' mismatch, not expecting clients to be in Social Engagement system functioning too soon. When therapists do not recognize the pathway to healing trauma and the important role of mismatch, those moments when “fighting” rhythms awaken from Shut-down can be wrongly experienced as threats to therapists.

Coming out of Shut-down can be messy and challenging; in this article, we present an explanation that is both theoretically and clinically grounded. Waking up the “fighting” rhythms after they have been inhibited by Shut-down is a risky process; many people find themselves spending years in fight/flight/shut-down, like in the case we presented. The ability of the therapist to remain with the client in this ‘messy’ process hopefully allows the client to evolve into Social Engagement system functioning. This may be equated to a second birth, and as such, it requires an accepting, smiling, and safe person to receive and invite entrance into Play/Dance.

References

Betty, A. (2013). Taming tidal waves: A dance/movement therapy approach to supporting emotion regulation in maltreated children. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 35(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-013-9152-3

Campbell, B. (2019). Past, present, future: A program development project exploring post traumatic slave syndrome (PTSS) using experiential education and dance/movement therapy informed approaches. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 41(2), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-019-09320-8

Contee, A., & Wagner, D. (2021). The neuroscience of healing multigenerational trauma through body-based practices. Counseling Today, 63(12), 12-15.

DeGruy, J. (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Uptone Press.

Devereaux, C. (2017a). An interview with Dr. Stephen W. Porges. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017-9252-6

Devereaux, C. (2017b). Neuroception and attunement in dance/movement therapy with autism. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(1), 36–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017- 9249-1

Diamond, L. (2015). The biobehavioral legacy of early attachment relationships for adult emotional and interpersonal functioning. In V. Zayas, & C. Hazan (Eds.), Bases of adult attachment: Linking brain, mind and behavior. (pp. 79-105). Springer.

Goldin-Meadow, S. (1997). When gesture and words speak differently. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 6(5), 138-143.

Goldin-Meadow, S. (2003). Hearing Gesture: How our hands help us think. Harvard University Press.

Gray, A. E. L. (2017). Polyvagal-informed dance/movement therapy for trauma: A global perspective. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(1), 43–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017-9254-4

Homann, K. B. (2010). Embodied concepts of neurobiology in dance/movement therapy practice. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 32(2), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-010-9099-6

Karr-Morse, R., & Wiley, M.S. (2012). Scared sick: The role of childhood trauma in adult disease. Basic Books.

Kestenberg Amighi, J., Loman, S., Lewis, P., & Sossin, K.M. (1999). The meaning of movement: Developmental and clinical perspectives of the Kestenberg Movement Profile. Gordon and Breach Publishers.

Kolacz, J., & Porges, S. W. (2018). Chronic diffuse pain and functional gastrointestinal disorders after traumatic stress: Pathophysiology through a polyvagal perspective. Frontiers in Medicine. 5, 145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00145

Kolacz, J., Kovacic, K., & Porges, S.W. (2019). Traumatic stress and the autonomic brain-gut connection in development: Polyvagal theory as an integrative framework for psychosocial and gastrointestinal pathology. National Library of Medicine, 61(5), 796- 809. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21852

Levine, P. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. (2017). Trauma and memory: Brain and body in a search for the living past. North Atlantic Books.

Loman, S. (2016). Judith S. Kestenberg’s dance/movement therapy legacy: Approaches with pregnancy, young children, and caregivers. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-016-9218-0

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago Press.

McNeill, D. (Ed.). (2000). Language and gesture. Cambridge University Press.

Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands: Racialized Trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. Central Recovery Press.

Payne, P., Levine, P. A., & Crane-Godreau, M. A. (2015). Somatic experiencing: using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 93.. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00093

Peters, W. D. (1991). A comparison of some portions of the developmental theories of Daniel N. Stern and Margaret S. Mahler (Publication No.ED332110) [Doctoral dissertation, Biola University]. Institute of Educational Sciences. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED332110

Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, self-regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Shahar-Levy, Y. (2001). The function of the human motor system in processes of storing and retrieving preverbal, primal experience. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 21(3), 378-393. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351692109348942

Tantia, J. F. (2012). Authentic movement and the autonomic nervous system: A preliminary investigation. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 34(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-012-9131-0

Tronick, E.Z. (1989). Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist, 44, 112–119.

Tronick, E. Z., & Cohn, J. F. (1989). Infant-mother face-to-face interaction: Age and gender differences in coordination and the occurrence of miscoordination. Child Development, 60(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131074

Tronick, E. Z., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Infants’ meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. American Psychologist, 66(2), 107-119. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021631

Tronick, E., & Gold, C. M. (2020). The power of discord: Why the ups and downs of relationships are the secret to building intimacy, resilience, and trust. Little, Brown Spark.

Wagner, D. (2015). Polyvagal theory and peek-a-boo: How the therapeutic pas de deux heals attachment trauma. Body Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 10(4), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2015.1069762

Wagner, D. (2017). The big dance: My love affair with the science of nervous-system functioning. Voices: The Art and Science of Psychotherapy, 53(1), 73-77.

Wagner, D. (2018, August 29). How fighting rhythms can help us navigate our binge-watching world. Elephant Journal. https://www.elephantjournal.com/2018/08/how-fighting- rhythms-can-help-us-navigate-our-binge-watching-world/

Wagner, D., & Hurst, S. M. (2018). Couples dance/movement therapy: Bringing a theoretical framework into practice. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 40(1), 18–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-018-9271-y

Wagner, D. (2021). “Mapping” nervous system responses: Finding a path to feeling better. In Miller & Beeson (Eds.), Neuroeducation toolbox: Practical applications of neuroscience for counselors and therapists (pp. 157-161), Cognella.

Waisman, O. S. (2010). Body, language and meaning in conflict situations: A semiotic analysis of gesture-word mismatches in Israeli-Jewish and Arab discourse. John Benjamins Publishing.

Waisman, O. S. (2014). Mismatches as milestones in dance movement therapy. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 9(4), 224-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2014.947324

Waisman, O. S. (2017). Mismatches between verbal and nonverbal signs, observing signs of change. Journal of Multimodal Communication Studies, 4(1-2), 75.